Former Yale basketball captain Jack Montague’s lawyer has filed his motion opposing summary judgment in his lawsuit against Yale. I’ve written extensively about the Montague lawsuit and won’t repeat my previous points. Instead, the post below will summarize some of the key items from attorney Max Stern’s lengthy brief and hundreds of pages of supplementary filings. You can read the brief here; the statement of facts is here.

Before looking through the filings, two reminders about the case:

- The critical procedural problem with the case from Yale’s perspective: the accuser didn’t want to file a complaint against Montague. Yale’s Title IX bureaucrats did. But Yale’s procedures appeared to preclude the Title IX office filing a complaint under the circumstances of this case. So how Yale would manipulate events to get a complaint against Montague was key.

- Montague had a previous disciplinary offense—as a freshman—that was presented as another instance of sexual misconduct, even though the actual facts of the case (shoving an empty pizza plate at the chest of a senior female student amidst a drunken argument) would hardly seem like the kind of case handled by Title IX tribunals, and were wholly different from this case. Nonetheless, that previous incident was used to encourage the accuser to participate in the process—and to justify the decision to expel Montague.

New Revelations

This case has been extensively litigated, but the Montague filings nonetheless contain several pieces of previously unrevealed information.

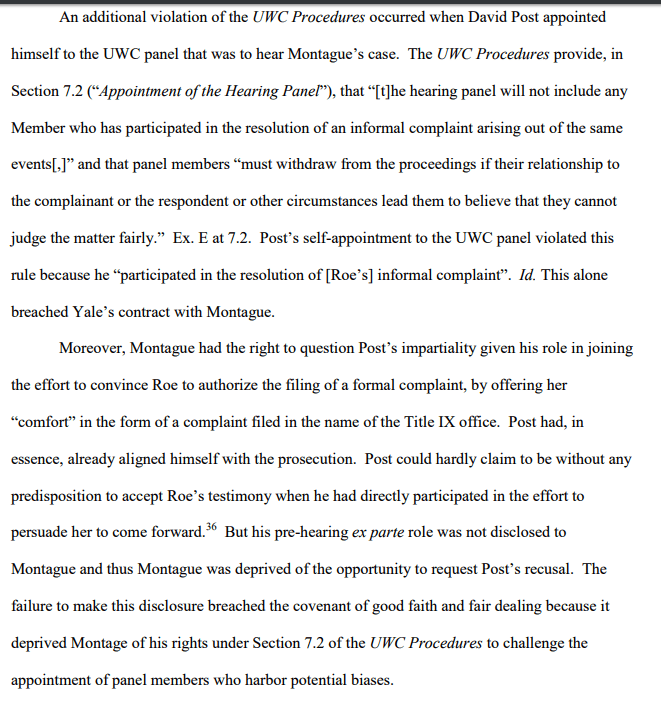

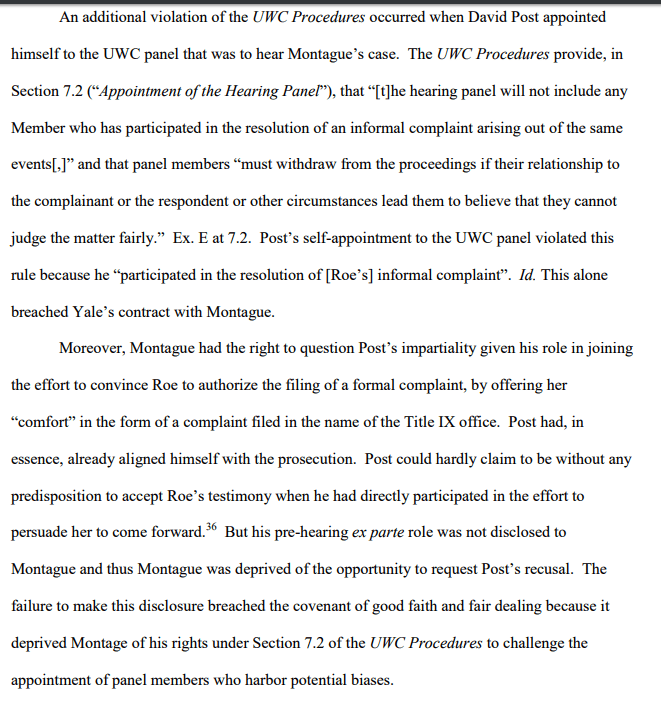

First: David Post, chair of the Yale Title IX tribunal (the UWC), was involved in the decision to encourage the accuser to participate in the disciplinary process—making himself available as a “standby” in a previously scheduled meeting between the accuser and a Title IX official, and then chatting with the accuser.

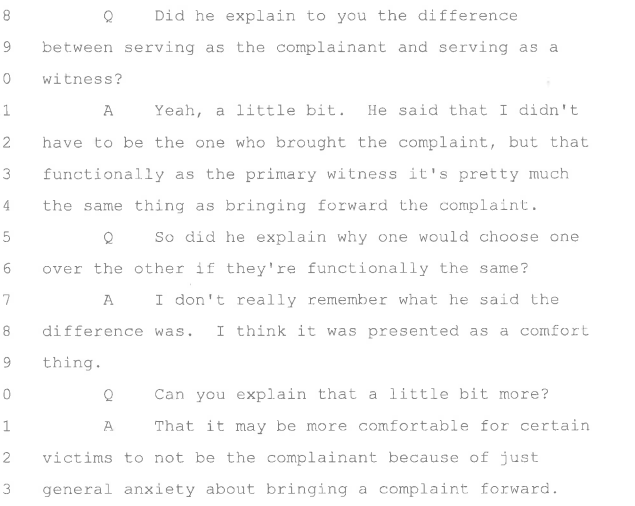

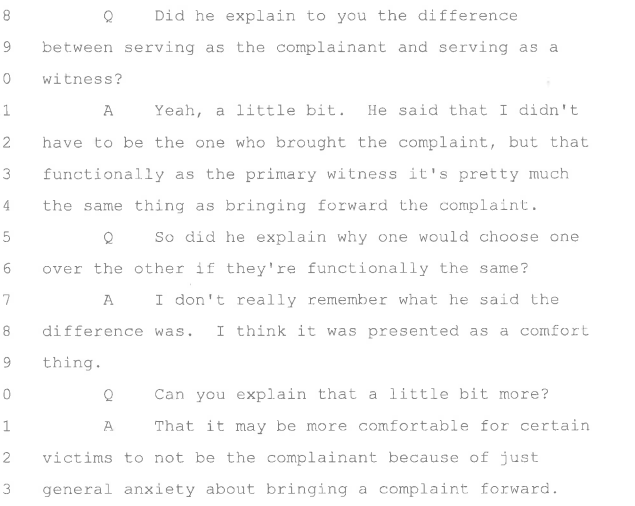

Second: Post suggested to the accuser that the university could adopt the procedures it ultimately did—the Title IX office filing the complaint, the accuser proceeding as a participating witness—for her “comfort.” Yet nothing in Yale’s then-existing procedures justified a “comfort” rationale, which appears to have been made up on the fly to maneuver the accuser into filing a formal complaint against Montague.

Third: Despite his involvement in the filing of the complaint, Post then participated in the Montague hearing as a member of the panel—without telling Montague of his role in bringing the charges in the first place.

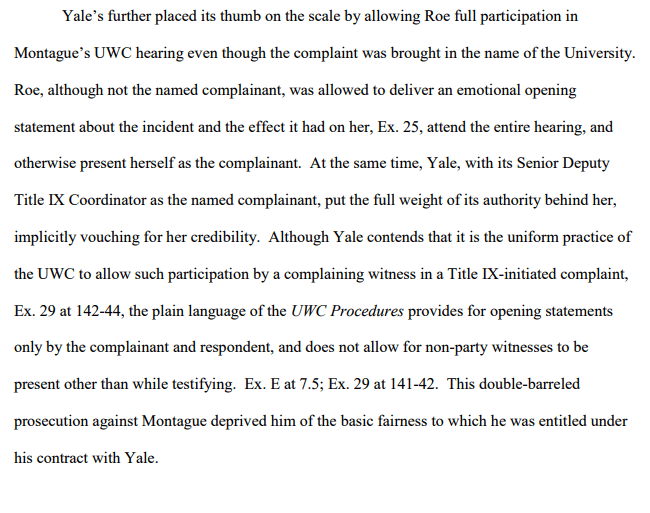

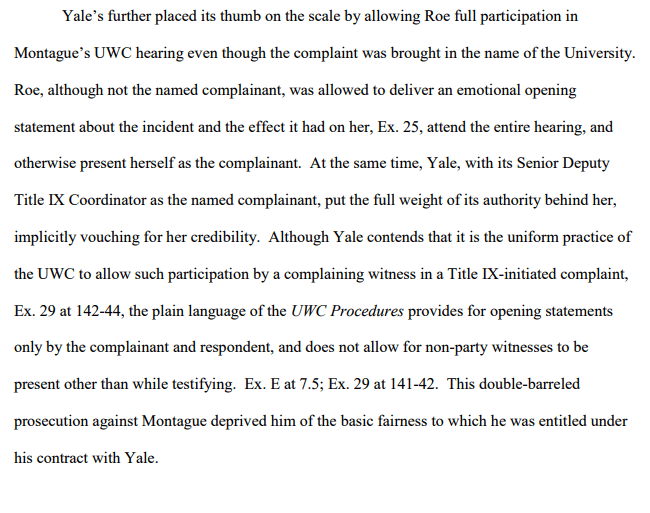

Fourth: Even though Yale’s Title IX office—not the accuser—was the “complainant” in the case, the accuser was given the procedural rights associated with complainants.

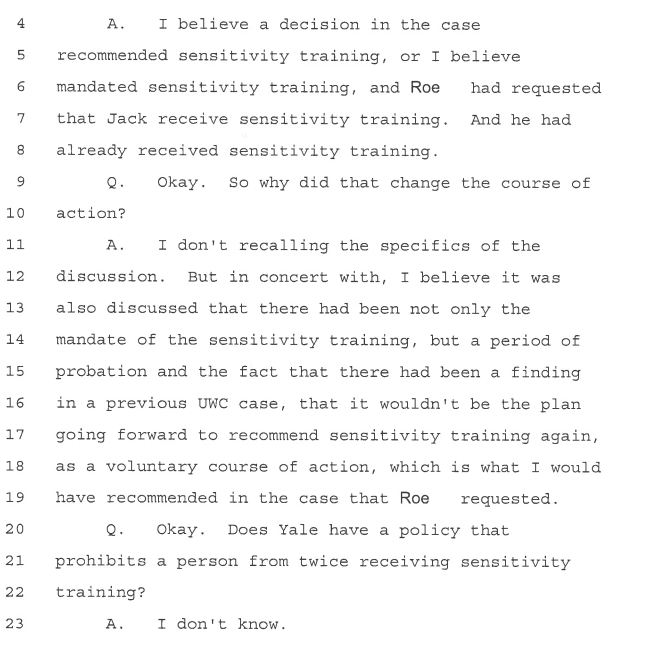

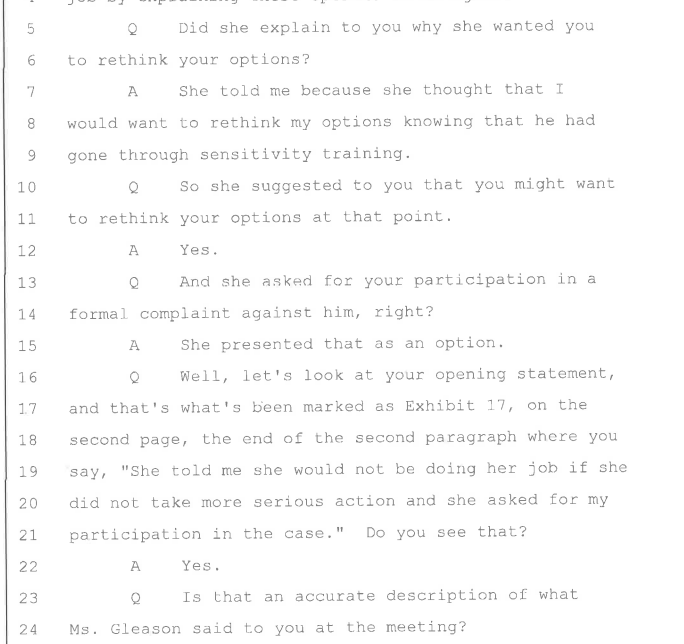

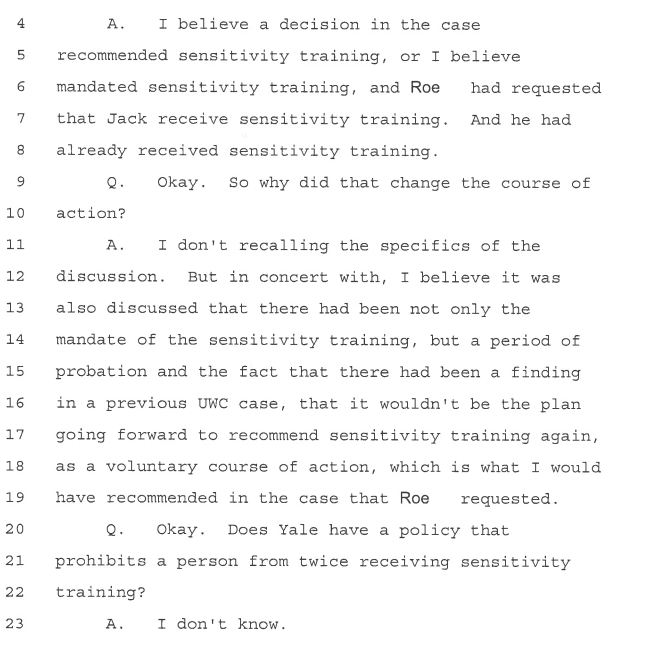

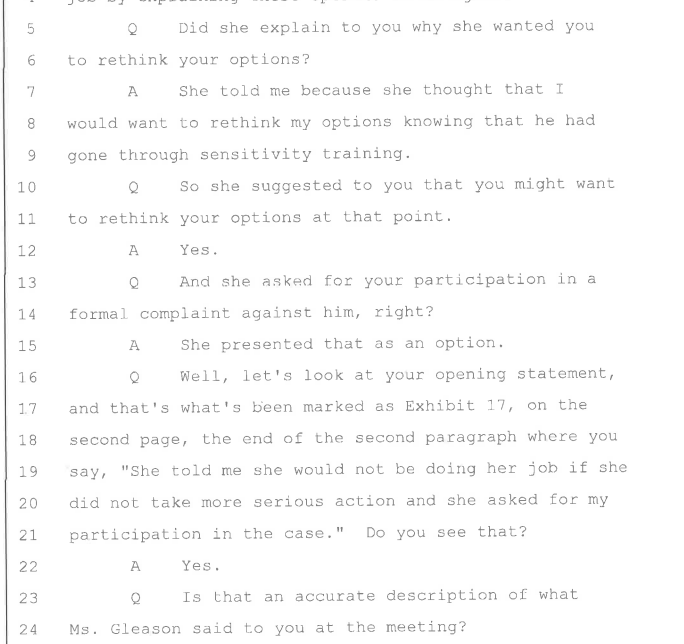

Fifth: The accuser initially said that she wanted only for Montague to receive “sensitivity training.” A Yale Title IX official (at the very least) told her that Montague previously had received training, and the office operated under the belief that it wouldn’t be appropriate for him to receive more. Yet the official admitted that she knew of no Yale policy that precluded two sets of training.

Fifth: The accuser initially said that she wanted only for Montague to receive “sensitivity training.” A Yale Title IX official (at the very least) told her that Montague previously had received training, and the office operated under the belief that it wouldn’t be appropriate for him to receive more. Yet the official admitted that she knew of no Yale policy that precluded two sets of training.

Sixth: Title IX officials knew that Montague was basketball captain at their meeting to brainstorm on how to ensure that a formal complaint was filed in the case; and a representative of Yale’s general counsel’s office participated in this meeting.

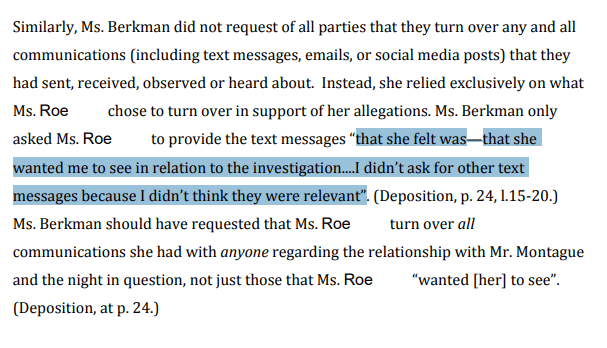

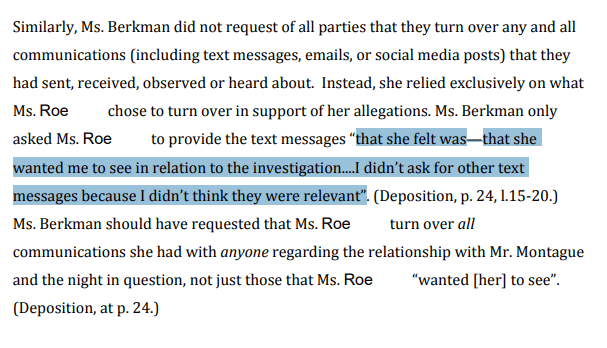

Seventh: Yale’s hired investigator, for reasons that are unknown, did not seek electronic evidence (text messages and the like) from the accuser or witnesses—and, indeed, testified that she allowed the accuser only to present texts that “she wanted me to see.”

Eighth: Even though Montague and the accuser had a preexisting sexual relationship, Yale’s investigator didn’t ask for their text history, and deemed pre-incident texts not “relevant” to her charge.

Ninth: While Yale Deputy Provost Stephanie Spangler contends that the Title IX office has no “view” on what process a campus accuser should follow, testimony from one of the Title IX officials involved in Montague’s case makes clear that for him, the office did have a preference—formal charges.

Brief

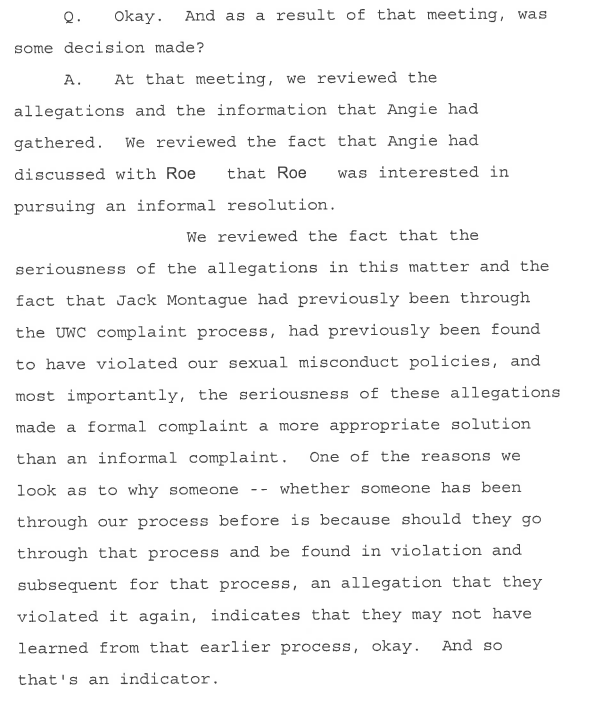

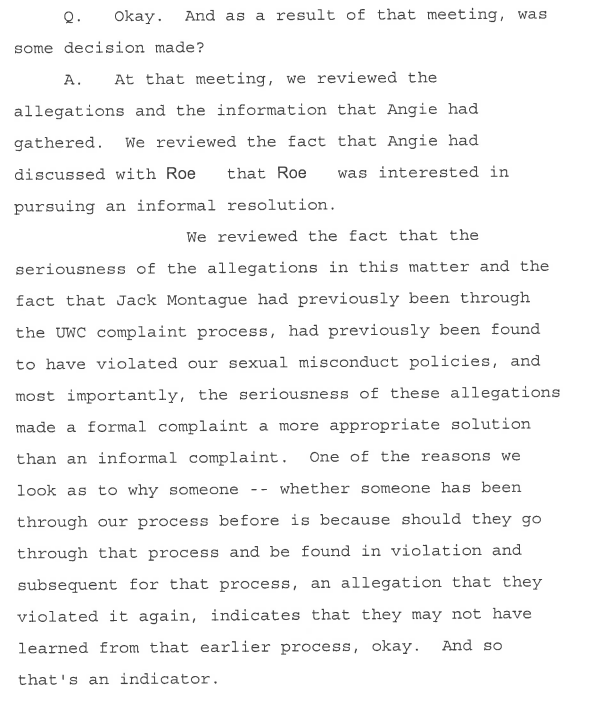

Stern’s brief provides a troubling summary of the key meeting of Title IX administrators to push the accuser into filing a formal complaint against Montague.

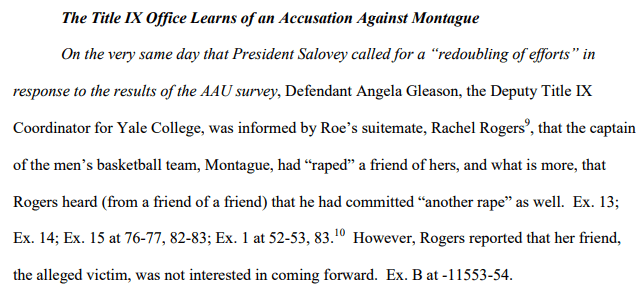

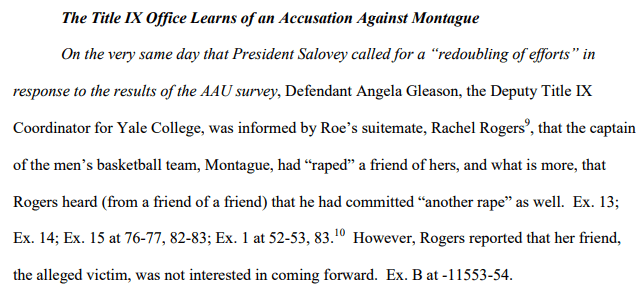

And, critically, the new filings hint at a reason why the university was so eager to bring charges against Montague—Title IX officials learned of a possible incident by this high-profile athlete on the same day that Yale’s president, hoping to deflect campus, media, and activist criticism, promised a “redoubling of efforts” to eradicate sex crime from campus.

The brief provides an intriguing citation of the recent Boston College decision, urging the court to adopt the First Circuit’s holding that universities must apply fundamental fairness in their Title IX adjudication processes.

And the brief also urges the court to respect the Second Circuit’s Columbia decision—an approach that one other district court, in the Colgate case, refused to do. Given the myriad accusers’ rights protests at Yale over the past several years, if Yale doesn’t meet the Columbia standard, no school does.

Montague’s First Disciplinary Action

The filings are very effective on the unfair way in which Yale officials used Montague’s first disciplinary infraction as an excuse to expel him.

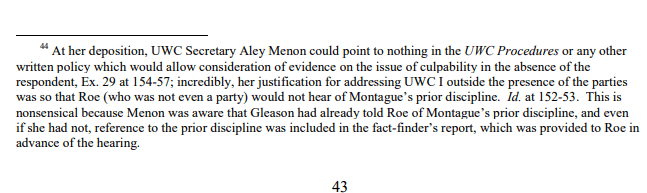

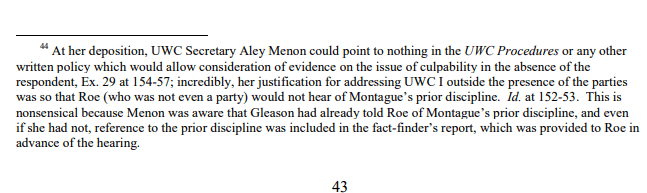

The brief notes that though the previous infraction was used to justify not only the punishment but the finding of guilt, Montague never received a chance to address it in the hearing.

Yale’s excuse for this approach—that the university respected Montague’s privacy rights—is comical.

The brief also supplies new evidence that Montague tried to bring to administrators’ attention the misuse of the first case in his appeals process, but the information never appears to have reached the appellate officer.

Finally, one exhibit provides contemporaneous emails from Yale administrators showing that the episode had nothing in common with the complaint that led to Montague’s expulsion.

The Accuser’s Convenient Change of Story

The brief notes—to a greater extent than done previously—how the accuser’s story was hardly consistent at the time.

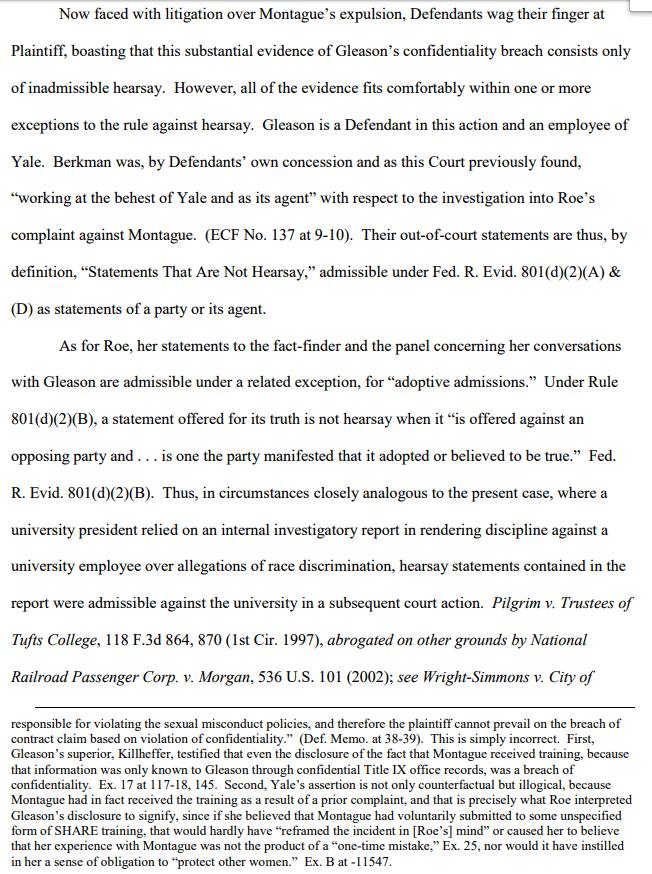

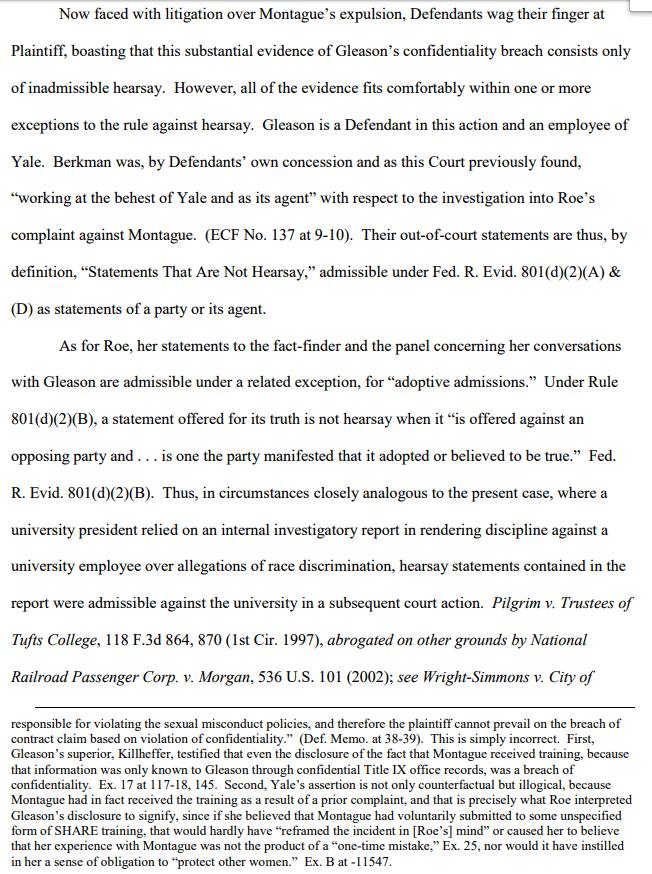

But significant sections of the filing also address the accuser’s convenient (for Yale) shift: that despite what the investigator said the accuser told her (that she participated in the formal process because a Yale Title IX official had told her about the earlier allegations against Montague—which would have violated both FERPA and Yale procedures), she was, in fact, never told such a thing. In her deposition, however, she admits that she was told he received “training”—which a Yale Title IX officer admitted shouldn’t have been done, and which she clearly interpreted as showing an earlier claim against Montague. So what was reported as the key reason why the accuser participated in the process in the investigator’s report is now, according to Yale, something that never happened at all.

The brief extensively discusses why the accuser’s sudden change of heart raises problems.

The accuser’s deposition also makes clear that Yale officials encouraged her to file a formal complaint.

Cleanup

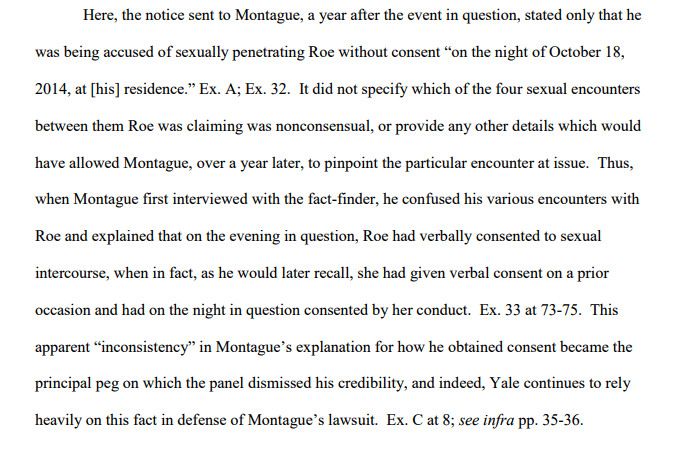

The filings tried to address two areas that Yale’s motion for summary judgment stressed: Montague’s credibility problems, and the admission by Montague’s expert that Yale’s procedures conformed to federal guidelines and would have justified expulsion if the accuser’s story was true.

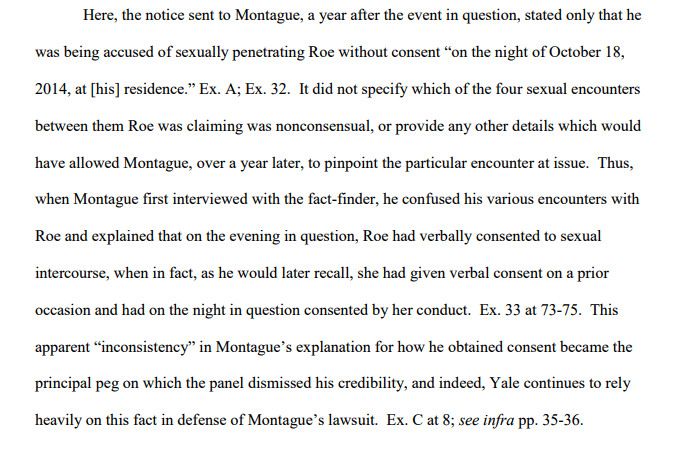

On the first point: the brief acknowledges that aspects of Montague’s statements to Yale weren’t consistent, but offers an explanation—that Yale never provided specific notice of the charges he faced, leading him to initially describe one sexual encounter with the accuser when the allegations involved another.

On the second: the brief stresses that the expert concluded that the investigation was biased, and therefore any finding of guilt had to be flawed.

The first of these areas seems more convincing than the second.

Yale Procedures

Two remarkable items from this filing speak to a one-sidedness that a university such as Yale would not tolerate in any academic context.

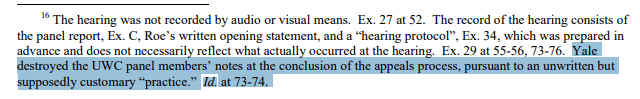

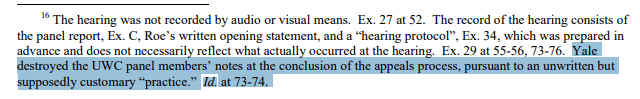

First: not only does Yale refuse to record or provide a transcript of its Title IX hearings, it also has a “practice” of requiring the panelists to destroy all their hearing notes. A cynical person might suggest they fear this material could be used in litigation.

Second: more than two years after this lawsuit was filed, Yale has still refused to turn over the “training” material given to Title IX panelists. Stuart and I wrote a piece on why this material is so important. The refusal is all the more remarkable given that Yale’s initial statements on the case highlighted the importance of this “training” material to ensuring a fair outcome.

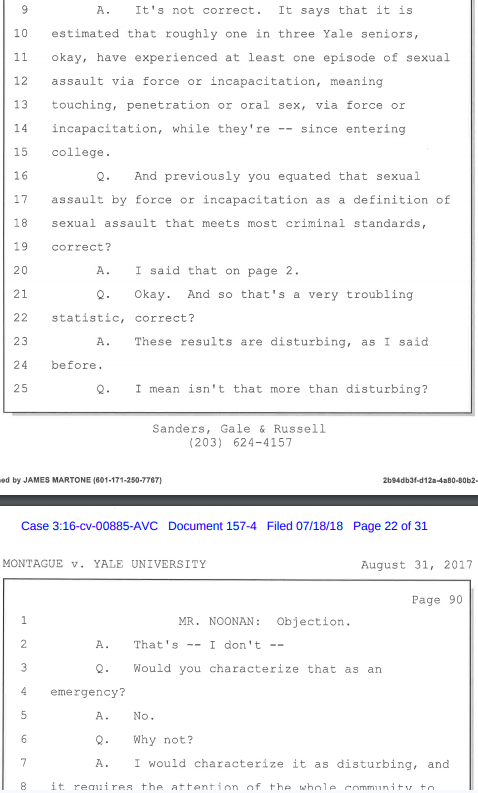

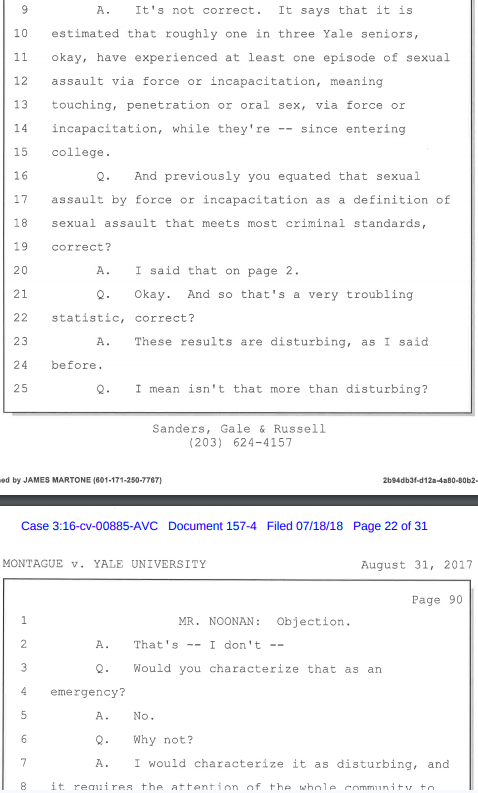

Additionally, this item from Stephanie Spangler shows how—when push comes to shove—even campus administrators don’t really believe the inflated figures they present about the number of sexual assaults on campus. Imagine any other context in which a high-ranking university official would say that 33 percent of female students being victims of violent crime didn’t constitute an “emergency.”

The Basketball Team

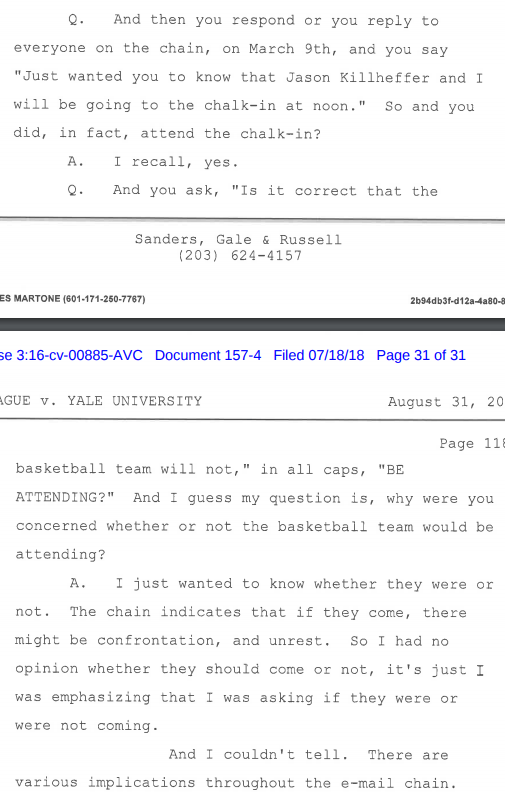

One important episode from the Montague case about which we still know little is the possibility of administrative pressure on the other members of the basketball team. After the expulsion, team members wore Montague’s number on their warmup shirts. This was, in its own way, a powerful, silent protest regarding the university’s mistreatment of Montague. But while in many contexts administrators might welcome their students standing up for due process, in this case strong campus opposition emerged, and the team quickly backed down. It remains unclear whether and how they were pressured to do so.

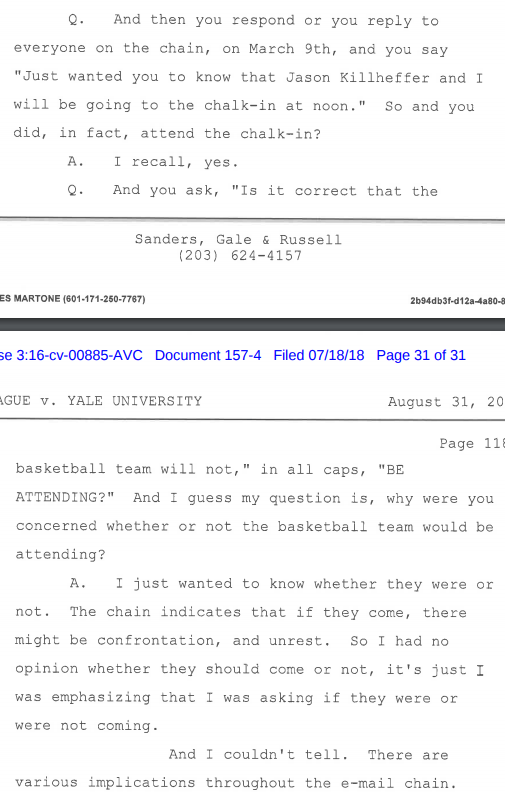

It’s clear from the deposition snippets contained as exhibits that members of the Yale administration knew of the players’ act. This one snippet, from Stephanie Spangler about a victims’ rights “chalk-in” following word of Montague’s expulsion, suggests a degree of disdain for the team among Yale’s Title IX bureaucracy:

Final Thoughts

These filings amplify rather than modify the basic narrative of the case: at a time when campus activists and media sympathizers were strongly criticizing the Yale administration as not tough enough on campus sex crimes, the university’s Title IX office learned that an allegation against Montague might exist. He presented a perfect target—as one of the highest-profile male students on campus., a guilty finding against him would demonstrate the university’s resolve and presumably soothe the criticism. But the accuser didn’t want to file a complaint. So university officials finessed their rules both to persuade the accuser to participate in the process and to bring charges against Montague at all. Once the complaint was filed, Montague had no chance—just as a guilty finding would demonstrate that the Title IX office, contrary to criticism, was serious about addressing the purported wave of violent crime on campus, a not-guilty finding risked intensifying that criticism.

Some of the New England cases—BC, Amherst, Johnson & Wales, Brandeis—feature overwhelming evidence of either innocence or massive procedural irregularities or (Amherst) both. This is not such a case. The facts associated with the allegation are ambiguous, and Yale’s procedural misconduct (focused on manipulating procedures to bring a case against a star male athlete to temper campus criticism) is subtler than most. Success for Montague will require a judge closely engaged with the issues raised in the lawsuit. To date, the 85-year-old Judge Alfred Covello has not been that jurist; his reasoning in the preliminary injunction denial was quite perfunctory, and his repeated description of the accuser as a “victim” suggested a prejudging of the outcome.

Montague has requested an oral argument.

Fifth: The accuser initially said that she wanted only for Montague to receive “sensitivity training.” A Yale Title IX official (at the very least) told her that Montague previously had received training, and the office operated under the belief that it wouldn’t be appropriate for him to receive more. Yet the official admitted that she knew of no Yale policy that precluded two sets of training.

Fifth: The accuser initially said that she wanted only for Montague to receive “sensitivity training.” A Yale Title IX official (at the very least) told her that Montague previously had received training, and the office operated under the belief that it wouldn’t be appropriate for him to receive more. Yet the official admitted that she knew of no Yale policy that precluded two sets of training.