As expected, Jack Montague, the former captain of the Yale basketball team, has filed a lawsuit against Yale, citing Title IX and breach of contract concerns resulting from his expulsion for sexual assault. This case—much like the Amherst case, also handled by Montague’s lawyer, Max Stern—has the potential to be significant, though for a different reason than Amherst. Using Yale’s own data, the complaint very plausibly alleges that Yale’s Title IX bureaucrats manipulated a female student in order to bring Montague up on disciplinary charges—and that they did so to avoid the negative publicity the university was receiving for allegedly being too “soft” on sexual assault. If the complaint can survive a motion to dismiss, the internal communications from Yale’s Title IX office could make for very revealing reading.

I’ve written about this case previously; and have written on Yale extensively. (You can read the full complaint here.) The university has a long history of going after high-profile athletes through dubious procedural tactics, dating back to the Patrick Witt case.

The heart of the complaint is this: “Montague found himself thrust into the confusing, terrifying, and lonely process through which those accused of sexual misconduct are maneuvered, and into the midst of Yale’s ongoing battle to establish itself as an institution that takes accusations of sexual misconduct seriously. Unfortunately for Montague, he was a prime candidate to serve as Yale’s poster boy for tough enforcement of its Sexual Misconduct Policies: popular, well-liked and respected amongst his peers at Yale, and known throughout the country as one of Yale’s most promising men’s basketball stars. In short, imposing harsh discipline on Montague would surely make an impact.”

The basics of the case: in fall 2014, Montague had a short-term sexual relationship with a female student. In September and October, the two spent the night together three times, and had some sort of sexual contact, including intercourse on at least one occasion. On the fourth time, in October, they had sexual contact but not intercourse in a car. They then went to Montague’s room, undressed, and had sexual intercourse.

The accuser would at some point conclude the intercourse was non-consensual (when remains a matter of dispute)—that she had wanted to hook up with Montague but not have sex with him. But even by her own admission, her method of communicating this intent, as she was laying alongside Montague in his bed, was virtually non-existent. During intercourse, she said that as she kissed Montague, touching his body consensually, she also “put her hands up, pressed them against the front of Mr. Montague’s shoulders and pushed him, but not very forcefully.” She also claimed that she told Montague she wanted to hook up but not have sex, but that he gave no indication that he heard her, as they were beginning intercourse. Montague claimed the sex was consensual.

In any event, after the disputed intercourse, the accuser returned to Montague’s room later that evening; they spent the night in his bed but she told him she didn’t want to have sex. He complied. A few days later, she said she hadn’t been comfortable having sex, and they stopped seeing each other. There was no indication that he harassed her (or had anything to do with her) over the next year.

Eleven months later, the accuser’s roommate was having a conversation with a Yale Title IX official (it’s not clear how many Title IX employees Yale has—according to the most recent report, Harvard has 50, so I’d imagine Yale’s total is comparable). The roommate told the official, Angela Gleason, that the accuser had a “bad experience” with Montague. Gleason met with the accuser around a month later, but the accuser made clear she didn’t want to file charges. So Gleason suggested Yale’s Kafkaeqsue “informal complaint” process—under which Witt was charged—in which the accused student is effectively presumed guilty and can’t present evidence of his innocence. The accuser agreed, provided that she could file her complaint anonymously, since she was “not interested in having Mr. Montague punished.”

At this point comes the heart of the case. Over the next few weeks, Gleason and/or her supervisors decided that they wanted to bring up Montague on formal charges, through the University-Wide Committee (UWC). According to the complaint, they misled the accuser into (a) believing that she couldn’t keep her identity confidential; and (b) that Montague had a past history of sexual misconduct towards women.

Montague did have a disciplinary past. But according to the complaint, the matter wasn’t sexual. The incident was from his freshman year, in public, when after a night of drinking he “rolled up a paper plate from the pizza parlor and put it down the front of [a graduating senior’s] tank top.” There was no sexual discussion or skin-to-skin contact, but Yale brought up Montague on charges of sexual harassment—oddly, since no one seems to have claimed that the incident was gender-related, or was anything more than petty drunken misconduct. He was placed on probation, and fulfilled the terms.

The accuser, however, appears to have believed that Montague had committed a sexual assault—based on what she was told by Yale officials. But she still declined to file charges against Montague. So the Title IX office came up with a plan to file charges independently. The accuser said she’d testify in a hearing, to “protect other women” from what appears to have been a non-existent threat.

To bring a case against Montague under these circumstances, Yale had to violate its own procedures. According to the Spangler Reports (the twice-yearly document about sexual misconduct cases Yale files as part of its OCR settlement), the Title IX officer can file only in “extremely rare cases,” and only when “there is serious risk to the safety of individuals or the community.” After charges were filed against Montague (but before the Title IX office’s involvement was public), Spangler told the Yale Daily News, “Except in rare cases involving an acute threat to community safety, coordinators defer to complainants’ wishes.” There clearly was no acute threat to community safety” from Montague.

Once Yale chose to file charges, Montague presumably had no chance: his exoneration would undermine what appears to have been the whole purpose of filing charges against him in the first place—to prove that the university was tough on sexual assault. We’ve heard a lot in recent weeks, especially because of events at Baylor, about how athletes receive special treatment on sexual assault. And sometimes, as at Baylor, they do. But this is a case in which Montague’s status as an athlete almost certainly worked against him, by making him an inviting target for the Title IX officials in a way that a normal student wouldn’t have been. His expulsion could send a broader message.

The complaint nonetheless brings to light deeply troubling aspects of Yale’s disciplinary approach. Montague had to give an interview with the Yale investigator without being informed of the specifics of the charges against him. The accuser appears to have been prompted to prepare an opening statement at the “hearing” Yale permits; Montague wasn’t told before the hearing he could do so. He couldn’t directly cross-examine his accuser; was represented by his coach (who couldn’t speak); and had no right to exculpatory evidence. The panel—specially “trained,” but with training material the university has never revealed—found him guilty. Yale then expelled him. The panel kept no audio or visual record of its “hearing.”

In its previous statements on the case, Yale has already telegraphed one element of its defense: the Spangler reports show that not everyone accused of sexual assault is expelled, so the university procedures aren’t biased against male students (so there’s no Title IX violation), or for that matter biased at all. The complaint, however, cleverly uses this same material—along with Yale’s own sexual assault scenarios—to show that, according to its own publicly stated guidelines, Yale should not have expelled Montague. Indeed, construing his behavior in the worst possible light, according to these guidelines he should have received a reprimand.

The conclusion of the case, of course, brought a witch-hunt atmosphere that recalled memories of the early days of the lacrosse case. When the basketball players did a silent tribute of personal support, they were roundly denounced. Anonymous students placed fliers on campus deeming Montague a “rapist.” (Now that they know the specifics of the allegations, would they still agree?) The Yale Women’s Center released a public statement deeming Montague’s expulsion “progress.” Unite Against Sexual Assault Yale termed it “exceptionally disappointing to see any display of support for anyone accused or convicted [sic] of sexual assault . . . It is the responsibility of every individual in the Yale community to take an active stand against sexually disrespectful behavior and sexual assault within their organizations and social circles.” In response, the basketball players released a hostage video-like statement, apologizing.

The general points:

(1) Yale had institutional reasons for wanting a target in fall 2015, and through the roommate’s chat with the Title IX official, Yale had its target. If this case survives a motion to dismiss, the e-mails from Yale administrators could make for explosive reading.

(2) The Title IX office’s filing charges against Montague violated the criteria laid out in the Spangler Reports and in Spangler’s public statement in February 2016. Yale hasn’t explained why it was so important to go after Montague that it needed to violate its own policies.

(3) The facts (at least as presented in the complaint, which appear to be largely undisputed) suggest that Montague was innocent. But even construing them in the worst possible light to him, Yale’s own public guidelines about appropriate punishments for particular types of sexual misconduct suggested he should have received a reprimand.

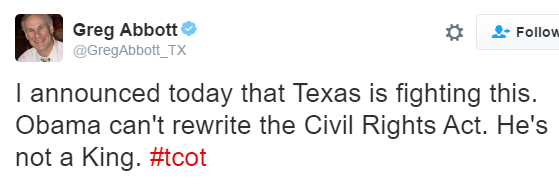

The case has been assigned to a Bush I appointee, Alfred Covello. Bush I judges have been all over the lot on this question (a Bush I appointee wrote one of the worst decisions on this issue, at Cincinnati), but it was critical for Montague to avoid the district’s chief judge, Janet Hall, who wrote a pioneering decision (involving, ironically, a case at Yale) that dramatically expanded the rights of accusers and provided some of the intellectual heft for the Obama administration’s efforts to eviscerate due process for accused students.